Effects of Marriage on Society

Marriage is the foundational relationship for all of society. All other relationships in society stem from the father-mother relationship, and these other relationships thrive most if that father-mother relationship is simultaneously a close and closed husband- wife relationship. Good marriages are the bedrock of strong societies, for they are the foundations of strong families. In marriage are contained the five basic institutions, all the basic tasks, of society: 1) family, 2) church, 3) school, 4) marketplace and 5) government. These fundamental tasks, well done, in unity between father and mother, make for a very good marriage. Within a family built on such a marriage, the child gradually learns to value and perform these five fundamental tasks of every competent adult and of every functional society.

1. Family

(See Effects of Divorce on Family Relationships)

Marriage enhances an adult’s ability to parent.1) Married people are more likely to give and receive support from their parents and are more likely to consider their parents as means for possible support in case of an emergency.2)

1.1 Related American Demographics

The National Survey of Children's Health showed that families with both biological or (adoptive) parents present have the highest quality of parent-child relationships.3) (See Chart)

The General Social Survey showed that adults who grew up living with both biological parents experience higher levels of marital happiness.4) (See Chart Below)

According to the General Social Survey (GSS), 72.6 percent of always-intact married adults believe in the importance of having their own children, followed by 70.8 percent of married, previously-divorced adults, 57.2 percent of single, divorced or separated adults and 35.2 percent of single, never-married adults. 5) (See Chart Below)

2. Church

(See Effects of Religious Practice on Marriage and Effects of Religious Practice on Family Relationships)

Social science shows that marriage has important implications for religious practice. Direct marriage (rather than cohabitation prior to marriage) has a positive effect on religious participation in young adults.6) Young adults raised in happily married families are more religious than young adults raised in stepfamilies,7) and attend religious services more frequently than those raised in divorced families.8) Young adults whose parents divorced prior to age 15 are much more likely than others to identify as “spiritual but not religious.”9) Those from married families are less likely to see religion decline in importance in their lives, less likely to begin attending church less frequently, and less likely to disassociate themselves from their religious affiliation.10)

2.1 Related American Demographics

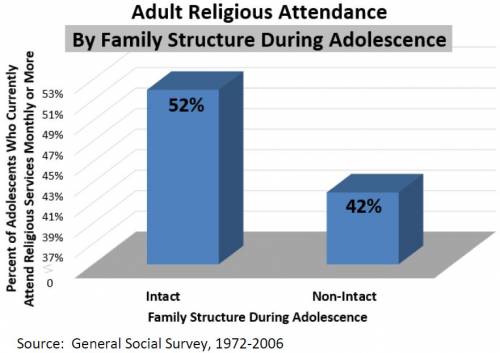

The General Social Survey shows that adults who attended religious services at least monthly as adolescents and grew up in an intact family are significantly more likely to attend religious services monthly or more frequently, as adults, than are those who attended less frequently and whose family of origin was non-intact. Additionally, those who attended religious services at least monthly as adolescents were substantially more likely to attend religious services as adults, regardless of whether they came from an intact or non-intact family. In other words, with regard to adult religious worship, frequent worship in adolescence significantly mitigates the negative effects of growing up in a non-intact family.11) (See Chart)

Looking at family structure alone shows that a larger fraction of adults who grew up in an intact married family than non-intact family attend religious services at least monthly.12) (See Chart Below)

3. School

(See Effects of Marriage on Children's Education, Effects Divorce on Children's Education, and Effects of Family Structure on Children's Education)

A greater fraction of children from intact married families earn mostly A’s in school,13) and children in intact married families have the highest combined English and math grade point averages (GPAs).14) Children from intact married families have the highest high school graduation rate,15) and are more likely to gain more education after graduating from high school than those from other family structures.16) Moreover, children of married parents are more engaged in school than children from all other family structures.17) Adolescents from intact married families are less frequently suspended, expelled, or delinquent, and less frequently experience school problems than children from other family structures.18)

4. Marketplace

(See Effects of Family Structure on the Economy)

Government and survey data overwhelmingly document that married-parent households work, earn, and save at significantly higher rates than other family households as well as pay most of all income taxes collected by the government. They also contribute to charity and volunteer at significantly higher rates, even when controlling for income, than do single or divorced households, leading Arthur Brooks of the American Enterprise Institute to write that “single parenthood is a disaster for charity.”19)

Married men are more likely to work than cohabiting men,20) and married fathers work more hours than cohabiting fathers.21) Children living with their two biological cohabiting parents are 263 percent more likely to experience poverty than children living with their two biological married parents. Likewise, children living with their married stepparents have significantly better economic outcomes than those living with cohabiting stepparents.22)

Additionally, married men earn more than single men.23) Men’s productivity increases by 26 percent as a result of marrying.24) Correspondingly, married families have larger incomes.25) Intact married families have the largest annual income of all family structures with children under 18.26) Married households have larger incomes than male and female householders.27) Married couples save more than unmarried couples,28) and married households have larger average net worth at retirement than other family structures.29) Young married couples tend to have goals for retirement and to save more for retirement than cohabiting couples or single people.30) Intact married families have the highest net worth of all families with children (widowed families excepted).31)

5. Government

5.1 Health Care

(See Effects of Marriage on Physical Health and Effects of Marriage on Mental Health)

Family intactness has a negative influence on, or reduces, an area’s fraction of 25- to 54-year-olds and minors receiving public healthcare,32) and a positive influence on an area’s fraction of 25- to 54-year-olds and minors with private healthcare coverage.33) Married men and women are also more likely to have health insurance.34) Furthermore, married individuals occupy hospitals and health institutions less often than others,35) are released from hospitals sooner, on average, than unmarried individuals,36) and spend half as much time in hospitals as single individuals.37) Married individuals are also less likely to go to a nursing home from the hospital.38)

5.2 Crime

(See Effects of Family Structure on Crime)

Marriage may diminish individual propensity to commit crime.39) For example, married men are less likely to commit crimes.40)

For children, living in a non-intact family is associated with an increased likelihood of committing violent and non-violent crime and the likelihood of drunk driving.41) Adolescents from intact families are less delinquent and commit fewer violent acts of delinquency.42) Correspondingly, a lower fraction of adults and youth raised in intact families are picked up by police than those from non-intact families.43)

5.2.1 Related American Demographics

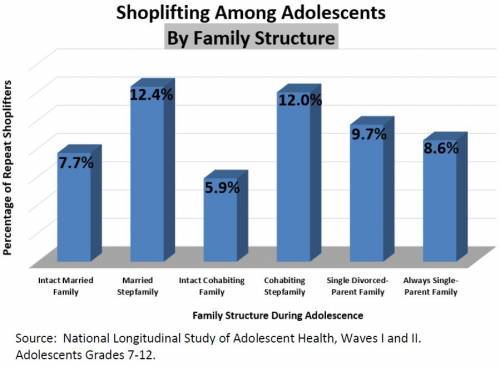

The Adolescent Health Survey showed that adolescents living in an intact married family steal less frequently than adolescents living in any other family structure.44) (See Chart)

Similarly, only eight percent of adolescents living with married parents and six percent of adolescents living with cohabiting biological parents are repeat shoplifters (3+ times), according to the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, Waves I and II.45) (See Chart Below)

5.3 Abuse

(See Effects of Family Structure on Child Abuse)

Marriage is associated with lower rates of domestic violence and abuse, in comparison to cohabitation.46) Domestic violence against ever-married mothers is lower than domestic violence against always-single mothers.47) In arguments, married couples are less likely to react physically (to hit, shove, or throw items) than cohabiting couples are.48)

Married women are murdered by their spouses at a far lower rate than cohabiting women are murdered by their partners,49) and in Canada, when couples of similar age are compared, murder is rarer among married than cohabiting couples. Similar results have been found in the U.S. Cohabiting women are 8.9 times more likely to be murdered by their partner than married women.50) Married women are less likely to have been forced to perform a sexual act (9 percent) than unmarried women (46 percent).51) Pregnant, married, non-Hispanic white and black women are less likely to be physically abused than those who are divorced or separated.52)

Compared to teenagers from intact families, teenagers from divorced families are more verbally aggressive and violent toward their romantic partners,53) and are more likely to have volatile and violent relationships in adulthood.54) Men raised in stepparent households are also more likely to have physical conflict in their romantic relationships.55)

Married parents are less likely to neglect their children than are divorced parents.56) Children in intact married families suffer less child abuse than children from any other family structure.57) British children were found to be less likely to be injured or killed by abuse in the intact married family than in all other family structures.58)

Nicholas Zill, “Quality of Parent-Child Relationship and Family Structure.” Available at http://marri.us/wp-content/uploads/MA-46-48-164.pdf. Accessed 1 September 2011.

Patrick F. Fagan and Althea Nagai, “Intergenerational Links to Marital Happiness: Family Structure,” Mapping America Project. Available at http://marri.us/wp-content/uploads/MA-31-33-159.pdf

Patrick F. Fagan and Althea Nagai, “The Personal Importance of Having Children by Marital Status.” Available at http://marri.us/wp-content/uploads/MA-79-81-175.pdf. Accessed 1 September 2011.

Jiexia Elisa Zhai, et al, “Spiritual, But Not Religious: The Impact of Parental Divorce on the Religious and Spiritual Identities of Young Adults in the United States,“ Review of Religious Research 49, no. 4 (June 2008): 390, 391.

Patrick F. Fagan and Althea Nagai, “Adult Religious Attendance by Religious Attendance and Family Structure in Adolescence,” Mapping America Project. Available at http://marri.us/wp-content/uploads/MA-70-72-172.pdf

Patrick F. Fagan and Althea Nagai, “Adult Religious Attendance by Family Structure in Adolescence.” Available at http://marri.us/wp-content/uploads/MA-70-72-172.pdf. Accessed 26 August 2011.

M. A. Monserud and G. H. Elder, “Household Structure and Children's Educational Attainment: A Perspective on Coresidence with Grandparents,” Journal of Marriage and Family no. 73 (2011): 988-990.

Brett V. Brown, “The Single-father Family: Demographic, Economic, and Public Transfer Use Characteristics,” Marriage and Family Review 29, (2000): 203-220.

W. D. Manning, and S. Brown, “Children’s Economic Well-Being in Married and Cohabiting Parent Families,” Journal of Marriage and Family no. 68 (2006): 351-352

Income and Poverty in the United States: 2013. U.S. Bureau of the Census, Current Population Reports, P60-249 (Issued September 2014). “Table 1, Income and Earnings Summary Measures by Selected Characteristics: 2012 and 2013.” Available at http://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2014/demo/p60-249.pdf Accessed 17 June 2015.

Matthew Painter, and Jonathan Vespa, “The Role of Cohabitation in Asset and Debt Accumulation During Marriage,” Journal Of Family & Economic Issues 33, no. 4 (December 2012): 491, 499, 503.

Precision has no formal meaning. It indicates how clearly determinable (distinguishable from zero) an influence on an outcome is. Precision is comparable to standard deviation. Low/ no precision indicates a high standard of deviation in which data points spread over a large range of value, signifying that the influence of one variable over another is relatively uncertain. High precision indicates a low standard of deviation in which data points hover around the mean, signifying that the influence of one variable over another is relatively certain. For further elaboration see “Marriage and Economic Well-Being: The Economy of the Family Rises or Falls with Marriage”

Henry Potrykus and Patrick Fagan, U.S. Social Policy Dependence on the Family, Derived from the Index of Belonging, (Washington, D.C.: Marriage and Religion Research Institute, 2013), 45-46. Available at http://marri.us/research/research-papers/u-s-social-policy-dependence-on-the-family/

Henry Potrykus and Patrick Fagan, “U.S. Social Policy Dependence on the Family, Derived from the Index of Belonging,” (2013). Available at http://marri.us/research/research-papers/u-s-social-policy-dependence-on-the-family/.

W. Forrest, “Cohabitation, Relationship Quality, and Desistance From Crime,” Journal of Marriage and Family no. 76 (2014): 547-549.

Patrick F. Fagan, “Family Structure and Theft.” Available at http://marri.us/wp-content/uploads/MA-22-24-156.pdf. Accessed 29 August 2011.

Patrick F. Fagan, “Family Structure and Shoplifting,” Mapping America Project. Available at http://marri.us/wp-content/uploads/MA-10-12-152.pdf

Todd K. Shackelford, “Cohabitation, Marriage, and Murder: Woman-Killing by Male Romantic Partners,” Aggressive Behavior 27, no. 4 (July 2001): 285, 288.

This entry heavily draws from 164 Reasons to Marry.