Effects of Religion on the Economy

Religious practice is an efficient and effective catalyst of socio-economic growth.1) In the United States religious organizations produce substantial economic revenue, provide substantial social capital through its civic and social networks, and foster human capital growth in its citizens.2) According to a 2016 estimate, faith-based organizations in the U.S. had a greater revenue than that of Apple and Microsoft combined.3) However, as government hostility toward organized religion has increased,4) religious affiliation has simultaneously decreased.5) This decline in religious practice will have significant negative repercussions for the U.S. economic framework.

1. Religious Liberty

Religious liberty contributes to better business and economic outcomes. According to Brian Grim of Georgetown University and Greg Clark and Robert Edward Snyder of Bringham Young University, countries with lower levels of religious hostilities and government restrictions on religion ranked stronger in global competitiveness.6) Religious freedom also contributed to peace and stability7) and helped lower corruption8)—two important ingredients for economic development. Research on Muslim-majority countries have shown that high religious restrictions deter young entrepreneurs9) and allow business competitors to cite religious laws to attack their rivals.10)

2. Social and Individual Norms that Boost Economic Growth

Religion affects economic decision-making by establishing social standards and shaping individual personalities. Firms located in communities with higher religiosity tend to adhere to ethical norms that are conducive to a stable economy. A 2015 study by Jeffrey Callen and Xiaohua Fang of the University of Washington found that companies headquartered in counties with higher religiosity had fewer instances of manager bad-news-holding and, correspondingly, significantly lower levels of future stock price crash risk.11) Banks headquartered in areas with high religiosity also took less risk and experienced less value destruction in times of crisis.12) Researchers at Rice University reported that companies headquartered in highly religious areas had fewer instances of “misbehavior” than those in less religious communities, as measured by securities fraud lawsuits filed against the firm, aggressive earnings manipulation, option back-dating, and excessive executive compensation.13) High religious adherence was also linked to a lower likelihood of financial restatement, less risk that financial statements were misrepresented, a lower likelihood of participating in tax sheltering, and more honesty in voluntary disclosures.14) Similarly, firms headquartered in religious areas had higher credit ratings and lower cost of debt.15)

Religious practice also naturally and efficiently cultivates the human capital necessary for a thriving economy. Religiously involved students tend to spend more time on their homework, work harder in school,16) and have higher educational aspirations.17) Religious practice is particularly powerful in helping disadvantaged youth in poor neighborhoods stay on-track in school and improve their educational status.18)

3. Revenue of Religious Organizations

In addition to instilling ethical norms and standards in employees and managers, religious organizations accrue significant revenue for the U.S. economy. In their 2016 analysis published in the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion, Brian and Melissa Grim calculated that faith-based organizations contributed $378 billion19) annually to the U.S. economy (based on revenue in education, healthcare, congregational activities, charities, media, and food).

Education: Based on school enrollment and tuition rates, Brian and Melissa Grim estimated that in 2011-2012 faith-based elementary schools made $15 billion, secondary schools made $12 billion, and higher education institutions made $46.8 billion.20)

Healthcare: Religious organization partner with public health institutions and provide health-related services and resources that promote physical and mental well-being.21) According to a 2014 report by Peter J. Brown of Emory University, the “Catholic Church—one of the largest health care providers—operated 5,246 hospitals, 17,530 dispensaries, 577 leprosy clinics, and 15,208 houses for the chronically ill and handicapped world-wide.”22) The 2014 annual revenue of U.S. faith-based hospitals and health systems with an active religious affiliation was $161 billion, according to Brian and Melissa Grimm’s calculations of the 100 top-grossing U.S. hospitals and the 100 top integrated health systems.23)

Congregational Activities: Based on data from the National Congregations Study cumulative dataset (1998, 2006-07, 2012) and 2010 Religious Congregations and Membership Study, Brian and Melissa Grim estimated that the average congregation spent $26,781 on social programs in 2012 (totaling $9 billion across the 344,894 congregations measured).24)

Charities: Of the fifty largest U.S. charities cited by Forbes magazine in 2014, twenty were faith-based. On the aggregate, these twenty charities made an annual revenue of $45.3 billion, reported Brian and Melissa Grim.25) Arthur Brooks of the American Enterprise Institute found that religious people were 25 percent more likely than their secular counterparts to donate money and 23 percent more likely to volunteer time. Even when it came to nonreligious causes, religious people were more generous.26)

Media: Revenue of faith-based media—including religious books, religious television networks (CBN and EWTN), and Christian/ Gospel music—was estimated at $0.9 billion, according to Brian and Melissa Grim’s calculations.27)

Food: Kosher (Jewish) and Halal (Muslim) food sales had a combined revenue of $14.4 billion (in 2014 and 2011, respectively). Food sales for various religious holidays also significantly impacts the economy.28) According to a 2013 estimate, Christmas purchases amounted to more than $3 trillion and led to the hiring of 768,000 additional employees.29)

4. Fair Market Value of Social Services of Religious Organizations

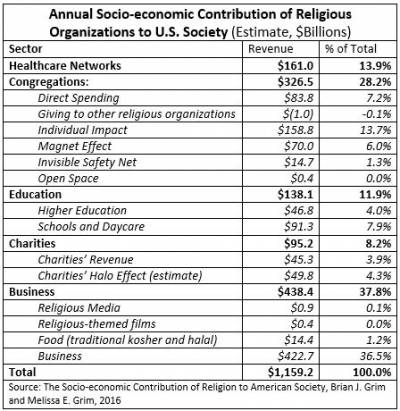

A more accurate valuation of the economic contribution of religious organizations is $1,159.2 billion, according to Brian and Melissa Grim’s 2016 study published in the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion. In addition to the hard-dollar revenue of religious organizations, this estimate factors in the fair market value of faith-based social services, the positive “halo effect” religious organizations have on a community by providing centers for education childcare, etc., and the economic contribution of businesses with religious roots.30) Dr. Ram A. Cnaan of the University of Pennsylvania has published a robust body of research examining the civic contribution of religious institutions to society.31) For example, in addition to worship services, congregations frequently provide adult and youth religious education, recruit volunteers, sponsor musical and artistic performances, host support groups for those struggling with drugs, alcohol, or abuse, provide marriage enrichment classes, sponsor groups for those with mental disabilities, deliver programs for the homeless, senior citizens, and immigrants, and fund disaster relief efforts.32)

In addition, a number of large for-profit businesses have a faith-based founding, even if the company does not overtly identify as religious. Businesses like Walmart, Tyson Foods, Tom's of Maine, and Whole Foods Market have religious roots that shape the company's managerial practices or operational conduct.33) (The table below summarizes the revenue derived from each sector studied.)

Through the social services and human capital they continuously build and maintain, religious organizations play a vital role in U.S. economic growth.