Effects of Family Structure on Crime

1. Broken Families and Crime

The scholarly evidence suggests that at the heart of the explosion of crime in America is the loss of the capacity of fathers and mothers to be responsible in caring for the children they bring into the world. This loss of love and guidance at the intimate levels of marriage and family has broad social consequences for children and for the wider community. The empirical evidence shows that too many young men and women from broken families tend to have a much weaker sense of connection with their neighborhood and are prone to exploit its members to satisfy their unmet needs or desires. This contributes to a loss of a sense of community and to the disintegration of neighborhoods into social chaos and violent crime. If policymakers are to deal with the root causes of crime they must deal with the rapid rise of illegitimacy.

Consider the following findings:

- Over the past fifty years, the rise in violent crime parallels the rise in families abandoned by fathers.

- High-crime neighborhoods are characterized by high concentrations of families abandoned by fathers.

- State-by-state analysis, by scholars from the Heritage Foundation, indicates that a 10 percent increase in the percentage of children living in single-parent homes leads typically to a 17 percent increase in juvenile crime.

- The rate of violent teenage crime corresponds with the number of families abandoned by fathers.

- The type of aggression and hostility demonstrated by a future criminal often is foreshadowed in unusual aggressiveness as early as age five or six.

- The future criminal tends to be an individual rejected by other children as early as the first grade who goes on to form his own group of friends, often the future delinquent gang.

On the other hand:

- Neighborhoods with a high degree of religious practice are not high-crime neighborhoods.

- Even in high-crime inner-city neighborhoods, well over 90 percent of children from safe, stable homes do not become delinquents. By contrast only 10 percent of children from unsafe, unstable homes in these neighborhoods avoid crime.

- Criminals capable of sustaining marriage gradually move away from a life of crime after they get married.

- The mother's strong affectionate attachment to her child is the child's best buffer against a life of crime.

- Strong parental bonds will significantly decrease the chance that the child will commit an act of violence.1)

1.1 Related American Demographics

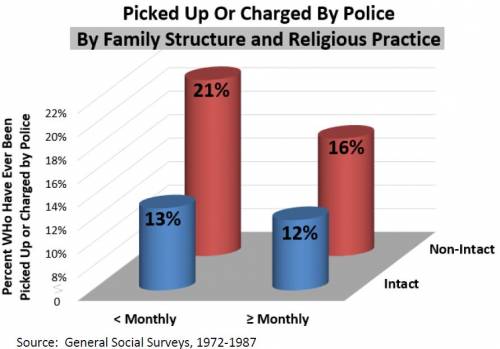

According to the General Social Surveys (GSS), 12 percent of adults who attended religious services at least monthly and lived in an intact family through adolescence have ever been picked up or charged by police, compared to 21 percent of adults who attended religious services less than monthly and lived in a non-intact family as adolescents.2) (See Chart Below)

2. Child Development

The propensity to commit crime develops in stages associated with major psychological and sociological factors. The factors are not caused by race or poverty, and the stages are the normal tasks of growing up that every child confronts as they get older. In the case of future violent criminals these tasks, in the absence of the love, affection, and dedication of both parents, become perverse exercises, frustrating the child's needs and stunting their ability to belong.

The stages are:

- Early infancy and the development of the capacity for empathy. Early family life and the development of relationships based on agreements being kept and a sense of an intimate place where he belongs. Early school life and the development of peer relationships based on cooperation and agreements conveying a sense of a community to which he belongs.

- Mid-childhood and the experience of a growing capacity to learn and cooperate within his community.

- Adolescence and the need to belong as an adult and to perform.

- Generativity, or the begetting of the next generation through intimate sexual union and bringing others into the family and the community.

Disruption during these stages cultivate a predilection for criminal behavior that leads to the demise of the community through a threefold process:

First, the broken family creates conditions to predispose children to criminal activities. Fatherless families with mother’s unable or unwilling to provide necessary affection, fighting and domestic violence, inadequate child supervision and discipline, and mistreatment of children are all common characteristics of broken families that also contribute to criminal activity.

Second, children who come from these broken families tend to have negative community experiences to further encourage their criminal participation. For example, they tend to face rejection from other children, struggle in school, and participate in gangs.

Ultimately, these conditions lead to the collapse of the community. Criminal youths tend to live in high-crime neighborhoods. Each reinforces the other in a destructive relationship, spiraling downward into violence and social chaos.

In all of these stages the lack of dedication and the atmosphere of rejection or conflict within the family diminish the child's experience of his personal life as one of love, dedication, and a place to belong. Instead, it is characterized increasingly by rejection, abandonment, conflict, isolation, and even abuse. The child is compelled to seek a place to belong outside of such a home and, most frequently not finding it in the ordinary community, finds it among others who have experienced similar rejection. Not finding acceptance and nurturance from caring adults, they begin conveying their own form of acceptance.

2.1 Related American Demographics

According to the General Social Surveys (GSS), 10 percent of adults who lived in an intact family as adolescents have ever been picked up or charged by police, compared to 17 percent of those who lived in a non-intact family.3) (See Chart).

The National Longitudinal Survey of Youth showed that 5 percent of youths who grew up in an intact married family had ever been arrested, followed by youths from married stepfamilies and families with intact cohabiting partners (8 percent), single divorced parent families (9 percent) and cohabiting stepfamilies and always single parent families (13 percent).4) (See Chart Below)

3. Forming Attachments

The evidence of the professional literature is overwhelming: teenage criminal behavior has its roots in habitual deprivation of parental love and affection going back to early infancy. Future delinquents invariably have a chaotic, disintegrating family life. This frequently leads to aggression and hostility toward others outside the family. Most delinquents are not withdrawn or depressed. Quite the opposite: they are actively involved in their neighborhood, but often in a violent fashion. This hostility is established in the first few years of life. By age six, habits of aggression and free-floating anger typically are already formed.5) By way of contrast, normal children enjoy a sense of personal security derived from their natural attachment to their mother. The future criminal is often denied that natural attachment.

The relationship between parents, not just the relationship between mother and child, has a powerful effect on very young children. Children react to quarreling parents by disobeying, crying, hitting other children, and in general being much more antisocial than their peers.6) And, significantly, quarreling or abusive parents do not generally vent their anger equally on all their children. Such parents tend to vent their anger on their more difficult children. This parental hostility and physical and emotional abuse of the child shapes the future delinquent.

Most delinquents are children who have been abandoned by their fathers. They are often deprived also of the love and affection they need from their mother. Inconsistent parenting,7) family turmoil,8) and multiple other stresses (such as economic hardship and psychiatric illnesses)9) that flow from these disagreements compound the rejection of these children by these parents,10) many of whom became criminals during childhood.11) With all these factors working against the child's normal development, by age five the future criminal already will tend to be aggressive, hostile, and hyperactive. Four-fifths of children destined to be criminals will be “antisocial” by 11 years of age, and fully two-thirds of antisocial five-year-olds will be delinquent by age 15.12)

According to the professional literature on juvenile delinquency, Kevin Wright, professor of criminal justice at the State University of New York at Binghamton, writes: “Research confirms that children raised in supportive, affectionate, and accepting homes are less likely to become deviant. Children rejected by parents are among the most likely to become delinquent.”13) This rejection and abandonment can cause the child to release his feelings through anti-social or delinquent behavior.14)

Many characteristics of broken families create the conditions for criminal behavior. Some of these include:

- Fatherlessness

- Absence of maternal affection

- Parental fighting and domestic violence

- Lack of parental supervision and discipline

- Rejection of the child

- Parental abuse or neglect

3.1 Related American Demographics

According to the Adolescent Health Survey, adolescents who live in an intact married family are less likely to steal than those living in step-families, those whose parents are divorced, or those raised by cohabiting parents.15) (See Chart)

The National Longitudinal Survey of Youth showed that 12 percent of adults who grew up with both biological parents married committed assault in their lifetime, followed by those who grew up in an intact, cohabiting family (14 percent), those who grew up in a divorced single-parent family (22 percent), those who grew up in a married stepfamily (23 percent), those who grew up in an alternate family structure [i.e. with grandparents, in foster homes, etc.] (26 percent), those who grew up with an always-single parent (29 percent), and those who grew up in a cohabiting stepfamily (34 percent).16) (See Chart)

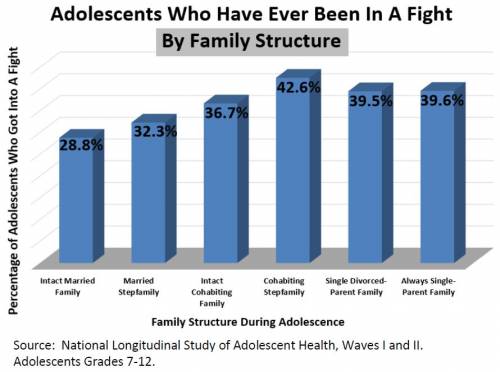

Analysis of the Adolescent Health Survey showed that youth who lived in an intact married family were least likely to get into a fight.17) (See Chart)

4. School Adjustment and Achievement

By the age of five or six, small children who are deprived of parental love and supervision have become hostile and aggressive and, therefore, have greater difficulty forming friendships with normal children. This hostility also undermines their school work and success. Professor David P. Farrington's Cambridge University study finds a high correlation between school adjustment problems and later delinquency: “Youths who dislike school and teachers, who do not get involved in school activities, and who are not committed to educational pursuits are more likely than others to engage in delinquent behavior.”18)

Children of single-parent families were far more likely to have academic and behavioral problems in school and were far more likely to become delinquents.19) On the contrary, children of intact married families are more likely to attend college.20) Future criminals tend not to have good verbal memory at school or the ability to grasp the meaning of concepts, including moral concepts. They generally fail to learn reading and computation skills, undermining their performance in the middle grades. They often fail in the later grades and have no or low aspirations for school or work.21) They begin to be truant and eventually drop out of school in their teens.22) Typically, before they drop out of school they already have begun a serious apprenticeship in crime by having far higher rates of delinquency than do those who graduate.23)

Once again, all these problems are rooted in unfavorable family conditions. In a study on juvenile delinquency, Merry Morash, professor of criminology at Michigan State University, analyzed four large data sets: the British-funded Cambridge Study of Delinquent Development and the U.S. federally funded National Longitudinal Study of Youth, National Survey of Children, and Philadelphia Cohort study. Examining these four large studies of the development of children, particularly the connection between home, education, and crime, she concludes: “[The] mother's [young] age is related to delinquency primarily through its association with low hopes for education, negative school experiences, father absence, and limited monitoring of the child.”24)

In 2013, 40.6% of all U.S. births were to unmarried women. Among Black women, roughly 71% of births were unmarried births, among Hispanic women that percentage drops to 53%, and among White women that percentage drops to 29% .25) A major revival of the intact married family is a necessary component of any policy initiative striving to reduce juvenile crime.

Patrick F. Fagan and Althea Nagai, “Intergenerational Links to Being Picked Up or Charged by Police: Religious Attendance and Family Structure,” Mapping America Project. Available at http://marri.us/wp-content/uploads/MA-55-57-167.pdf

Patrick F. Fagan and Althea Nagai, “Intergenerational Links to Being Picked Up or Charged by Police:Family Structure,” Mapping America Project. Available at http://marri.us/wp-content/uploads/MA-55-57-167.pdf

Rolf Loeber, “Development and Risk Factors of Juvenile Antisocial Behavior and Delinquency,” Clinical Psychology Review 10, (1990): 1-41.

Cynthia Osborne, Sara McLanahan, and Jeanne Brooks-Gunn, “Young Children’s Behavioral Problems in Married and Cohabiting Families,” Center for Research on Child Well-Being Working Paper 03-09 (2005).

Wendy D. Manning and Kathleen A. Lamb, “Adolescent Well-Being in Cohabiting, Married, and Single-Parent Families,” Journal of Marriage and Family 65, no. 4 (2003): 876-893.

Patrick F. Fagan, “Family Structure and Theft,” Mapping America Project. Available at http://marri.us/wp-content/uploads/MA-22-24-156.pdf

Patrick F. Fagan, “Family Structure and Fighting,” Mapping America Project. Available at http://marri.us/wp-content/uploads/MA-13-15-153.pdf

Rolf Loeber, “Development and Risk Factors of Juvenile Antisocial Behavior and Delinquency,” Clinical Psychology Review 10, no. 1 (1990): 1-41.

Sandra L. Jofferth, “Residential Father Family Type and Child Well-Being: Investment Versus Selection,” Demography 43, no. 1 (2006): 53-77.

Donna K. Ginther, “Family Structure and Children’s Educational Outcomes: Blended Families, Stylized Facts, and Descriptive Regressions,” Demography 41, no. 4 (November 2004): 671-696.

Yongmin Sun and Yuanzhang Li, “Children’s Well-Being During Parents’ Marital Disruption Process: A Pooled Time-Series Analysis,” Journal of Marriage and Family 64, (2002): 472-488.

Suet-Ling Pong and Gillian Hampden-Thompson, “Family Policies and Children’s School Achievement in Single- Versus Two-Parent Families,” Journal of Marriage and Family 65, (2003): 681–699.

Julie Artis, “Maternal Cohabitation and Child Well-Being Among Kindergarten Children,” Journal of Marriage and Family 69, no. 1 (2007): 222-236.

Shannon E. Cavanagh and Aletha C. Houston, “Family Instability and Children’s Early Problem Behavior,” Social Forces 85, no. 1 (2006): 551-581.

Sandra L. Hofferth, “Residential Father Family Type and Child Well- Being,” Demography 43, no. 1 (2006): 53-77.

Marcia J. Carlson and Mary E. Corcoran, “Family Structure and Children’s Behavioral and Cognitive Outcomes,” Journal of Marriage and Family 63, no. 3 (2001): 779-792.

Susan L. Brown, “Family Structure and Child Well-Being: The Significance of Parental Cohabitation,” Journal of Marriage and Family 66, no. 2 (2004): 351-367.

Shannon E. Cavanagh and Kathryn S. Schiller, “Marital Transitions, Parenting, and Schooling: Exploring the Link Between Family- Structure History and Adolescents’ Academic Status,” Sociology of Education 79, no. 4 (2006): 329-354.

Toby Parcel and Mikaela Dufur, “Capital at Home and at School: Effects on Student Achievement,” Social Forces 79, no. 3 (2001): 881-911.

Suet-Ling Pong and Gillian Hampden-Thompson, “Family Policies and Children’s School Achievement in Single- Versus Two-Parent Families,” Journal of Marriage and Family 65, no. 3 (2003): 681-699.

Suet-Ling Pong and Gillian Hampden-Thompson, “Family Policies and Children’s School Achievement in Single- Versus Two-Parent Families,” Journal of Marriage and Family 65, no. 3 (2003): 681-699.

This entry draws heavily from The Real Root Causes of Violent Crime: The Breakdown of Marriage, Family, and Community.