Table of Contents

Effects of Religious Practice on Work Ethic

The beneficial effects of religious practice on education are transmitted to the individual student through various pathways within the family of origin and through peers, the church community, and the extended community. There are also a number of individual pathways that play an important role in harnessing the benefits of religious practice.

1. Values and Norms

Internalized values and norms have a significant impact on math and reading scores, both directly1) and indirectly, through the effect that values have on other school-related activities such as homework, watching television, and reading.2) Just as secular “personal morality” has a positive impact on school attendance,3) so do “religious values,” which are among the variables that influence behaviors outside of school (such as watching television less, doing homework more, reading, and working for pay). All of these, in turn, affect high-school students’ achievement.4)

2. Locus of Control

Values also help form an internal locus of control. “Locus of control” is the presence of established habits of discipline and balance in matters of work and initiative. Sandra Hanson, Professor of Sociology at Catholic University of America, and Alan Ginsburg, Director of the Policy and Program Studies Service within the U.S. Department of Education, explain that “[a] high internal locus of control refers to the belief that one’s action and efforts, rather than fate or luck” shape the result of one’s efforts. This belief, in turn, is linked to “the effort that students put forth and the importance they assign to working hard.”5)

Religious practice increases adolescents’ sense of an internal locus of control. In a panel study of Iowa families, Glen Elder, Professor of Sociology and Psychology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and Rand Conger, Professor of Psychology, Human Growth, and Family Studies at the University of California Davis, conclude that “[r]egular participation in church services and programs strengthened self-concepts of academic achievement, work habits, and discipline.”6) Mark Regnerus also found that, in addition to fostering stronger social bonds with family and community, a higher level of involvement in church activities is associated with “a level of social control and motivation toward education that leads to better math and reading skills.”7) Another study concludes that adolescents’ religious involvement is positively associated with a sense of control over their lives.8)

3. Expectations

Teens who are devoutly religious have higher educational expectations for themselves.9) Among Vietnamese immigrants, frequent religious attendance correlates to adolescents’ placing a greater importance on attending college, earning good grades, and avoiding substance abuse.10)

The presence of those with religious beliefs has similar effects. Youth in schools where the majority are Jewish are 14 percent more likely to plan to attend college than counterparts in schools where Jewish students are a minority. This influence toward education is not diminished and indeed is even slightly increased when the normal controls for intelligence, mother’s aspiration, occupation, and income are taken into account.11) A study on Catholic identity showed outcomes similar to the result of the Jewish study, with regard to expectations for increased educational achievement.12)

4. Skills and Habits

Certain habits correlate with good school performance, such as attending school regularly and spending more time on homework. Religious practice helps form these habits, as an analysis of inner-city children who escape poverty illustrates: “Church-going invariably raises the amount of time a youth spends on productive activity [working, searching for work, traveling to work, school-going, housework, and reading].”13)

Another study showed that regular participation in church services and programs strengthens work habits and self-discipline.14)

Religious attendance also appears to boost social skills: Elder and Conger report from the Iowa longitudinal study that religiously-involved eighth-grade students have greater social skills in the twelfth grade.15) These studies all agree that religious practice (and all that comes with it) delivers highly valued habits and skills that enhance social life, study, and earnings.

4.1 Related American Demographics

According to the National Survey of Children’s Health, children who attend religious services at least weekly score higher on the social development scale (50.7) than children who never attend religious services (48.4). In between are children who worship one to three times a month (49.6) and children who attend religious services less than once a month (49.7).16) (See Chart)

5. Behavior

Religious attendance has a profound effect on children with behavioral risks. One study analyzed the characteristics of those who escape poverty and found that church attendance powerfully reduces socially deviant activity.17) Another showed that while religious practice has a positive protective influence across all income levels, it proves particularly effective in engendering educational resilience among at-risk youths.18)

Even among low-risk, middle-class adolescents, religious attendance has a significant effect on minimizing behavioral risks. One study found that adolescents who attended weekly religious services were less likely to use drugs or alcohol, to engage in delinquent behavior, to get in trouble at school or to have poor grades when compared with their peers who attended church less than monthly or not at all. Youth who considered religion to be fairly important or very important in their lives were less likely to engage in risky behavior.19) For many of these youth, church attendance “reinforces messages about working hard and staying out of trouble, orients [youth] toward a positive future, and builds a transferable skill-set of commitments and routines.”20)

For youth from more advantaged homes and communities, it is the importance they place on religion which has the greater impact on positive behavioral outcomes, rather than church attendance alone. For advantaged students, a high “importance of religion” score reduces the likelihood of alcohol use, drug use, delinquency, and problem behaviors at school.21)

5.1 Related American Demographics

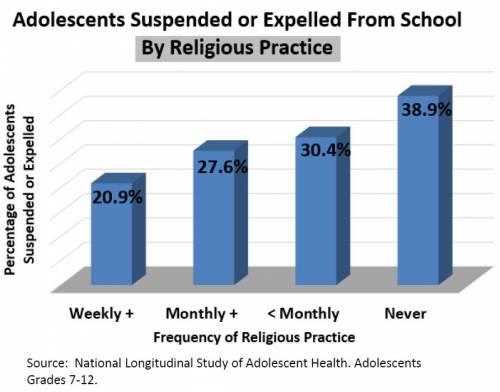

Adolescents who worship at least weekly are least likely to be expelled or suspended from school. According to the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, 21 percent of students in Grades 7-12 who worship at least weekly have ever been suspended or expelled. By contrast, almost 39 percent of adolescents who never worship have been suspended or expelled.22) (See Chart)

Nicholas Zill, “Children's Positive Social Development and Religious Attendance,” Mapping America Project. Available at http://marri.us/wp-content/uploads/MA-58-60-168.pdf

Patrick F. Fagan, “Religious Attendance and Expulsion or Suspension from School,” Mapping America Project. Available at http://marri.us/wp-content/uploads/MA-19-21-155.pdf

This entry draws heavily from Religious Practice and Educational Attainment.