Table of Contents

Effects of Religious Practice on Education

Because education is important for all citizens and the government invests heavily in public schooling, any factor that significantly promotes academic achievement is important to the common good. A growing body of research has consistently indicated that the frequency of religious practice is significantly and directly related to academic outcomes and educational attainment. Religiously involved students spend more time on their homework, work harder in school,1) and achieve more as a result.2)

1. Educational Achievement

Increased religious attendance is correlated with higher grades.3) In one study, students who attended religious activities weekly or more frequently were found to have a GPA 14.4 percent higher than students who never attended.4) Students who frequently attended religious services scored 2.32 points higher on tests in math and reading than their less religiously-involved peers.5)

More than 75 percent of students who become more religious during their college years achieved above-average college grades.6) Religiously involved students work harder in school than non-religious students.7)

1.1 Related American Demographics

According to the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, students who attended religious services weekly or more had a higher average GPA than those who attended religious services less frequently.8) (See Chart)

The National Longitudinal Survey of Youth also showed that 26 percent of students who worshiped at least weekly received mostly A’s, followed by those who attended religious services between one and three times a month (21 percent), those who attended religious services less than once a month (18 percent), and those who never attended religious services (16 percent).9) (See Chart Below)

Similarly, teenagers who attended religious activities weekly or more had the highest average combined GPA for English and Math (2.9), while those who never attended religious activities had the lowest (2.6).10) (See Chart Below)

2. Educational Attainment

Popular opinion holds that the more educated people are, the less religious they are. However, according to the Pew Research Center,11) college-educated Christians in the United States are as—and in some cases more—observant that less educated Christians.12) Frequent religious practice is positively correlated with higher educational aspirations.13) Students who attended church weekly while growing up had significantly more years of total schooling by their early thirties than peers who did not attend church at all.14) Both Jews and Christians are more likely to receive higher education than are the Unaffiliated.15) Attending religious services and activities positively affects inner-city youths’ school attendance, work activity, and allocation of time—all of which are further linked to reduced likelihood to be deviant.16)

Frequent religious attendance correlates with lower dropout rates and greater school attachment.17) Similarly, frequent religious attendance resulted in a five-fold decrease in the likelihood that youth would skip school, compared to those who seldom or never attended.18)

2.1 Related American Demographics

According to the National Survey of Children's Health, parents whose children attended worship at least weekly were less likely to be contacted by their children’s school about behavior problems than parents whose children worshiped less frequently.19) (See Chart Below)

The National Longitudinal Survey of Youth showed that 87 percent of students who attended weekly religious services received a high school degree. They were followed by those attended at least monthly (81 percent), those who attended less than monthly (76 percent), and those who never worshiped.20) (See Chart Below)

The same survey revealed that 32 percent of individuals who attended weekly religious services had received a Bachelor’s degree, compared with those who attended religious services at least monthly (27 percent), those who attended less than once a month (19 percent), and those who never attended (14 percent).21) (See Chart Below)

3. Religious Families

3.1 Non-Religious Motivations for Religious Practice

Religion increases the family’s human capital in many ways. For instance, religiously involved parents were more likely to plan successfully for the future and to structure their children’s activities in ways that increased their children’s likelihood of taking advanced math courses and graduating from high school.22) Another study showed that family cohesion, which religious practice increases, is associated with increased internal locus of control and academic competence among youth. Family cohesion also influenced the way youth dealt with problems.23)

A parent who is “intergenerationally altruistic”—that is, cares about the welfare of the child—will participate in religious practice to build up the requisite amount of human capital necessary for a child to become “skilled” (i.e., part of the non-manual labor market). Thus, the future of the child’s education and income are a positive incentive for parents to attend religious activities. Incentive is diminished only if the parent is convinced that the child has no possibility of becoming “skilled,” or if the child has no expressed desire to become “skilled.”24) Therefore, altruistic parents can and often will be religious, even if they have little intrinsically religious motivation to be so, in order to transfer the social capital benefits of religious practice to their children.

3.1.1 Related American Demographics

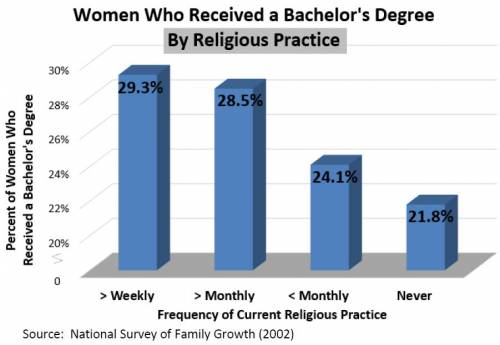

According to the National Survey of Family Growth, 29.3 percent of women aged 35-44 who worshiped at least weekly had attained a bachelor’s degree, followed by those who attended religious services between one and three times a month (28.5 percent), those who attended religious services less than once a month (24.1 percent), and those who never attended religious services (21.8 percent).25) (See Chart)

3.2 Parents' Expectations

In their study of secular academic performance, Hanson and Ginsburg of Catholic University and the US Department of Education found that parental educational expectation was among the factors that had the strongest impact on adolescents’ high-school outcomes.26) The greater the parents’ religious involvement, the more likely they would have higher educational expectations for their children and would communicate with their children about their education.27) Christian Smith of Notre Dame University, moreover, found that parents’ church attendance increased the probability that their adolescent children knew more clearly what their parents expected and that their parents would be upset if they were sexually involved, used drugs, drank alcohol, got into fights, or skipped school.28)

3.3 Family Structure

Marital stability is another form of human capital that advances educational attainment, while its opposite, divorce, hinders it.29) Religious practice plays its part here also. Religious heterogamy (when the spouses belong to different denominations) increases the likelihood of divorce,30) while homogamy (when both spouses are members of the same denomination) increases the likelihood of marital stability and happiness.31)

Carmel Chiswick, Professor of Economics at the University of Illinois at Chicago, found that “[p]eople with high levels of religious human capital tend to select spouses who also have high levels, forming family units for which the home production of religious education is more efficient.”32) This phenomenon of high homogamy and practice seems to be operating in the American home-schooling movement.33) It also has led to less conflict and greater happiness for couples,34) as well as better relationships between children and parents.35) In turn, this adds to family satisfaction, which has a larger effect than any of the religious variables in protecting against risky behaviors that undermine educational attainment.36)

4. Religious Communities

4.1 Religious Schools

Attendance at religious schools influences educational performance and attainment. Significant literature exists detailing the strength of Catholic education in advancing the academic achievement of its pupils.37) One study described the supportive network of such parochial and private schools as equivalent to a “social neighborhood” that reduces youths’ risks and promotes academic achievement.38) Throughout a large body of literature investigating the comparative educational effectiveness of religious and secular schools, findings such as the following are typical: “Roman Catholic students in Catholic controlled schools are more likely to plan for college than Catholic pupils in public schools—even if Catholics are in the majority at the public school.”39)

In addition, religious schooling has a positive long-term impact on adolescents’ religiosity, especially in high school, and especially if students receive a considerable amount of classroom instruction in religion.40) Low-income students in schools that “stress academics and religion, possess high student morale, and encourage the centrality of religion and the development of community of faith” tend to be more committed to their faith and church than their counterparts in schools that do not have such emphases.41) It is not surprising, then, that a 2015 Rasmussen Report found that 61 percent of parents with school-aged children believe there should be more religion in public schools.42)

4.2 Peers

Good friendships, peer networks, and youth associations that help adolescents live more fully engaged lives, while discouraging risky behavior, may have a positive effect on educational outcomes. Though the area of peer relationships has received some attention throughout the past 50 years, most research has focused on dysfunctional behaviors and behavioral interventions. The social science understanding of the operations and dynamics of positive friendships are limited.43) Within the limited body of research available, however, there are indications that networks of religious peers yield positive benefits. One study showed that a student’s values, as well as peers’ values, can have positive effects on out-of-school behaviors.44) Another study reported that peers’ values mediate, in part, the positive effect of religious involvement on teens’ educational expectations.45) Elder and Conger also demonstrated that religious values influence youths’ perception of their friends and that, even at this stage of their lives, they develop future marriage plans in light of their religious beliefs.46) Another study discovered that youth participation in religious activities promotes friendships that “aid and encourage academic achievement and engagement.”47)

Religious participation also increases intergenerational closure, a term that describes an adolescent’s affinity for his parents and his parents’ friends. Intergenerational closure, then, encourages role modeling and mentorship, within both the parent-child relationship and relationships with other adults. Religion provides a pathway for children to interact constructively with both their peers and their superiors, which generally encourages improved academic performance.48)

4.3 Extracurricular Activities

Structured after-school activities, including religious activities, are also associated with better educational outcomes. In an analysis of data from the National Educational Longitudinal Study of 1988, student participation in structured activities, religious activities, and activities with adults during tenth grade had a significant positive impact on educational outcomes when those students were in the twelfth grade.49) Participation in extracurricular activities produced a greater increase in youths’ educational expectations than participation in church activities did, although both types of activities had a significant positive impact.50) Conversely, students who spent more unstructured time (e.g., hanging out with peers) were at greater risk of performing poorly in school.51)

Extracurricular church activities help youth reduce those problem behaviors that were putting their academic attainment at risk. The benefits of extracurricular church activities were dramatically demonstrated by one study that found that youths who were highly involved in church-sponsored organizations outside of school had a low level of problem behaviors. While their academic and psychological competence scores were lower than those of peers categorized as “academically competent,” their engagement level in extracurricular activities and community programs distinguished them positively from their peers.52)

A study of high school seniors in the 1988 National Educational Longitudinal Study showed that positive perceptions of religion and frequent attendance at religious activities were related to the following: a) positive parental involvement, b) positive perceptions of the future, c) positive attitudes toward academics, d) less frequent drug use, e) less delinquent behavior, f) fewer school attendance problems, g) more time spent on homework, h) more frequent volunteer work, i) recognition for good grades, and j) more time spent on extracurricular activities.53)

4.4 The Church Community

The community of church members, like the family, plays its part in advancing educational attainment. The strong social bonds of religious groups can supplement the resources available to children, especially those in large families, helping them to achieve higher levels of education.54) Participation in church activities benefits children in all neighborhoods of different income levels, though it particularly benefits children in low income neighborhoods.55) Interviews with black college students found that their religious communities fostered academic success by providing role models and mentors.56)

Elder and Conger provided a detailed account of the effect of the church community on adolescents’ attitudes, expectations, and academic achievement:

Surrounded by adults and peers who care about worthy accomplishments, religiously-involved youth tend to score higher than other adolescents on school achievement, social success, confidence in self, and [parents’ report of their] personal maturity57)… Regular participation in church services and programs strengthened self-concepts of academic achievement, work habits, or discipline… Within the church, young people found guidance and encouragement from congregation members with whom they established strong ties.58)

When they asked the high school freshmen they surveyed to estimate how their peer groups would rank five activities—athletics, school activities, working hard to get good grades, community activities, and church activities—adolescents who were not involved in the church and youth group were most likely to rank athletics first and school activities second.59) In contrast, religiously-involved students gave a higher rank to both education and church activities.60)

Being anchored in a religious community promotes positive relationships among adolescents. One study found that the greater a high school student’s engagement in church activities, the stronger his or her peer competence.61) Similarly, high school seniors who performed well academically and socially were more likely to have had greater exposure to the disciplines and objectives of the church and the church youth group, and to associate with peers who shared those values.62)

For immigrant youth and other ethnic groups, the church or synagogue is often the preferred place to study the language of their heritage and their community. This simultaneously contributes to the formation of a cultural and a religious identity and, as a result, increases the likelihood of educational achievement.

In their study of Vietnamese immigrant youth, Carl Bankston, Professor of Sociology at Tulane University, and Min Zhou, Professor of Sociology and Asian American Studies at the University of California Los Angeles, found that, while church attendance and parents’ membership in a church correlated to higher grade point averages, church-sponsored programs in language and culture mediated part of the benefit. Rather than impeding the upward mobility of youth, these activities correlated strongly and positively to adolescents’ academic performance. Bankston and Zhou explained this dynamic:

Ethnic religious participation … promotes adjustment to the host society, precisely because it promotes the cultivation of a distinctive ethnicity, and membership in this distinctive ethnic group helps young people reach higher levels of academic achievement and avoid dangerous and destructive forms of behavior.63)

Religious affiliation is important to the cultivation of welcoming communities. Western Christians are less intolerant of contradiction and more willing to take on different perspectives than their Atheist/ Agnostic counterparts.64)

Related to the community and culture effect is Jonathan Gruber’s finding that residing in an area where the demographic majority reflects one’s religious tradition was associated with significantly greater religious involvement and with better outcomes with regard to education, income, and marital status.65)

4.5 Disadvantaged Communities

For youth in impoverished neighborhoods, religious attendance made the greatest difference in academic achievement prospects, according to research in 2001 by Regnerus. As rates of unemployment, poverty, and female-headed households grew in a neighborhood, the impact of a student’s level of religious practice on academic progress became even stronger.

Regnerus posits that churches uniquely provide “functional communities” for the poor that reinforce parental support networks, control, and norms in environments of disadvantage and dysfunction. In these neighborhoods, families are most likely to build pathways to success for their children when they closely monitor them and when they develop ties to local churches that expose their children to positive role models. Youth in high-risk neighborhoods who regularly attend religious services progress at least as satisfactorily as their peers in low-risk, middle-class neighborhoods:

“Religious attendance was found to serve as a protective mechanism in high-risk communities in a way that it does not in low risk ones, stimulating educational resilience in the lives of at-risk youth. We argue that adolescents’ participation in religious communities—which often constitute the key sources of neighborhood developmental resources—reinforces messages about working hard and staying out of trouble, orients them toward a positive future, and builds a transferable skill set of commitments and routines.”66)

Regnerus went on to suggest that religious affiliation had a positive impact on educational attainment for African–Americans residing in a high-risk neighborhood, even when controlling for family structure, although its effect was strongest for youth living in two-parent families.67) The role of religion in building relationships and habits of hard work “reinforces a conventional (as opposed to alternate or illegal) orientation to success and achievement.” Youth religious affiliation in combination with religious families and friends serves to integrate youth into the broader society and shapes their aspirations for education and achievement.68)

5. Work Ethic of Students

(See Effects of Religious Practice on Work Ethic)

The beneficial effects of religious practice on education are transmitted to the individual student through various pathways within the family of origin and through peers, the church community, and the extended community. For at-risk youth, religious practice reduces socially deviant behavior.69) Regular religious attendance increases the internalization of traditional values and norms, strengthens a sense of internal locus of control and discipline, and increases adolescents’ expectations of higher educational achievement for themselves. In these ways, religious practice is a positive force for staying on track in school.

J.L. Glanville, D. Sikkink, and E.I. Hernández, “Religious Involvement and Educational Outcomes: The Role of Social Capital and Extracurricular Participation,” Sociological Quarterly 49, (2008): 105-137.

Patrick F. Fagan, “Religious Attendance and School Performance of U.S. High School Students,” Mapping America Project. Available at http://marri.us/wp-content/uploads/MA-1-3-149.pdf

Nicholas Zill, “Parents Contacted by School about Their Children’s Behavior Problems and Religious Attendance,” Mapping America Project. Available at http://marri.us/wp-content/uploads/MA-52-54-166.pdf

Patrick F. Fagan and D. Paul Sullins, “'Mothers (aged 35-44) Who Have Attained a Bachelor’s Degree' by Religious Attendance and Present Family Structure,” Mapping America Project. Available at http://marri.us/wp-content/uploads/MA-92.pdf

Timothy J. Biblarz & Greg Gottainer, “Family Structure and Children’s Success: A Comparison of Widowed and Divorced Single-Mother Families,” Journal of Marriage and Family 62, (2000): 533-48.

Evelyn L. Lehrer & Carmel U. Chiswick, “Religion as a Determinant of Marital Stability,” Demography 30, no. 3 (1993): 385-404.

This entry draws heavily from 95 Social Science Reasons for Religious Worship and Practice, Religious Practice and Educational Attainment, and Why Religion Matters Even More: The Impact of Religious Practice on Social Stability.